How Mary Elizabeth Braddon invented sensation fiction and got erased from the literary canon

I was scrolling through a list of Victorian bestsellers when I came across a name that stopped me: Mary Elizabeth Braddon. According to the article, her novel Lady Audley’s Secret was one of the most popular books of the 1860s, outselling even Charles Dickens. She wrote over 80 novels, was translated into multiple languages, and was apparently so famous that Oscar Wilde name-dropped her in The Importance of Being Earnest.

My first thought was, “Who the hell is Mary Elizabeth Braddon?”

My second thought was that familiar sinking feeling I get whenever I discover another brilliant woman writer who somehow got written out of the history I was taught in school.

The Queen of Sensation

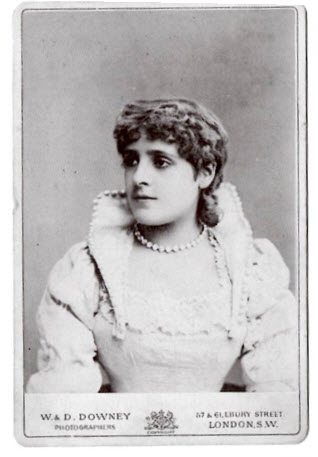

Here’s what should be common knowledge but isn’t: Mary Elizabeth Braddon (1835-1915) essentially invented what we now call psychological thriller novels. She was writing about domestic violence, women’s rage, and the dark secrets lurking behind respectable facades decades before anyone called it “women’s fiction” or “domestic noir.”

Her breakthrough novel, Lady Audley’s Secret, published in 1862, tells the story of a beautiful young woman who marries an older, wealthy man and then—spoiler alert for a 160-year-old book—turns out to be a bigamist and potential murderer with a history of mental illness. It was scandalous, addictive, and absolutely revolutionary for its time.

The book was so popular that it spawned multiple stage adaptations, countless imitations, and an entire genre called “sensation fiction.” Braddon didn’t just write a bestseller—she created a literary movement that would influence everything from gothic horror to modern psychological thrillers.

But ask any English literature student today about Victorian sensation fiction, and they’ll probably mention Wilkie Collins or maybe Bram Stoker. Braddon, despite being the genre’s most successful and prolific writer, has somehow become a footnote in her own movement.

The Woman Behind The Scandal

What makes Braddon’s story even more compelling is how her own life reads like one of her sensation novels. Born to a struggling middle-class family, she became an actress in her teens to support herself and her mother—a scandalous profession for a respectable woman in Victorian England.

She started writing serialized novels for cheap magazines, churning out melodramatic stories to pay the bills. But unlike other writers who looked down on popular fiction, Braddon embraced it. She understood that entertainment and art weren’t mutually exclusive, and she wrote books that were both gripping page-turners and sharp social commentary.

In her personal life, she lived with publisher John Maxwell for years before they could marry (his wife was in an asylum), raising his children from his first marriage alongside their own six children. By Victorian standards, she was living in sin while writing some of the most morally complex fiction of her era.

She was, in other words, a woman who refused to be contained by social expectations—and her writing reflected that same refusal to be limited by literary conventions.

What She Actually Did

Braddon didn’t just write popular novels—she revolutionized what popular novels could be. Lady Audley’s Secret was one of the first books to suggest that the real monsters weren’t supernatural creatures lurking in gothic castles, but ordinary people living in ordinary houses with extraordinary secrets.

Her heroines weren’t passive victims waiting to be rescued. They were complex, often morally ambiguous women who took action—sometimes terrible action—to control their own destinies. Lady Audley herself is sympathetic and terrifying, a woman driven to desperate measures by the limited options available to her in a patriarchal society.

Braddon was also one of the first writers to explore what we’d now call mental health issues with nuance and empathy. Instead of simply making her characters “mad” for plot convenience, she examined how trauma, poverty, and social pressures could affect someone’s psychological state.

She understood that the most compelling stories often happened behind closed doors, in the spaces between what people present to the world and what they’re actually thinking and feeling. Sound familiar? It should—she was basically writing domestic psychological realism 50 years before Virginia Woolf.

The Critical Backlash

Of course, the very things that made Braddon popular with readers made her suspect to literary critics. Her books were dismissed as “sensational” (hence the genre name), meaning they were considered crude, commercial, and appealing to base emotions rather than elevated artistic sensibilities.

The fact that her primary audience was women didn’t help her critical reputation. Victorian literary culture had a clear hierarchy: serious literature was written by men for educated male readers, while popular fiction was seen as frivolous entertainment for women and the working classes.

Braddon’s crime wasn’t just writing popular fiction—it was writing popular fiction that took women’s experiences seriously. Her books suggested that women’s lives, women’s desires, and women’s anger were worthy subjects for literature. This was deeply threatening to the literary establishment that preferred women as muses rather than creators.

Even worse, from the critics’ perspective, she was making a fortune doing it. Braddon was one of the first women writers to achieve real financial independence through her work, which challenged the romantic notion that true art required suffering and poverty.

The Disappearing Act

So how does someone who sold millions of books and influenced an entire literary movement simply vanish from cultural memory? The answer is depressing. The same forces that have erased countless women’s contributions to culture throughout history.

First, there was the academic gatekeeping. When English literature became a formal academic subject in the early 20th century, scholars focused on creating a “canon” of important works. Popular fiction—especially popular fiction written by women—was systematically excluded as insufficiently serious or artistic.

Then there was the genre problem. Sensation fiction was reclassified as “genre fiction,” which marked it as less important than “literary fiction.” Never mind that Braddon’s psychological insights were as sophisticated as any “serious” novelist of her time—she was writing about murder and bigamy, so it couldn’t be art.

Finally, there was the timing issue. Braddon’s peak popularity coincided with the rise of new literary movements like realism and modernism. Critics became interested in writers who were experimenting with form and style, not writers who were perfecting traditional narrative techniques to create maximum emotional impact.

By the time feminist scholars started recovering “lost” women writers in the 1970s, Braddon had been forgotten for so long that even they weren’t sure how to position her. Was she a feminist pioneer or a writer of escapist fantasies? Was she a serious artist or a commercial hack? The truth, of course, is that she was all of these things.

What We Lost

Reading Braddon now, what strikes me most is how contemporary her concerns feel. She was writing about women trapped in marriages they couldn’t escape, about the psychological toll of domestic violence, about the ways poverty and limited options can drive people to desperate choices.

She understood that women’s anger was a legitimate subject for literature, that the divide between public respectability and private truth was worth exploring, and that the most interesting stories often centered on people that society prefers to ignore or dismiss.

Her influence on later writers is undeniable once you start looking for it. The domestic gothic tradition that runs from Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper through Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle to contemporary writers like Gillian Flynn owes a debt to what Braddon pioneered.

She proved that popular fiction could be psychologically sophisticated, that entertainment and social commentary could coexist, and that women’s experiences of violence and oppression were worthy of serious artistic treatment.

That Books That Started It All

If you want to understand what made Braddon revolutionary, start with Lady Audley’s Secret. It’s available free online and reads like a Victorian version of Gone Girl—a psychological thriller about a woman whose seemingly perfect life conceals devastating secrets.

What’s remarkable about the novel is how it balances sympathy for its protagonist with genuine horror at her actions. Lady Audley is both victim and villain, a woman whose desperate circumstances don’t excuse her choices but do help explain them.

The book moves at a pace that would make contemporary thriller writers jealous. Still, it pauses to examine questions about women’s legal status, mental health treatment, and the limited options available to women without independent means. It’s entertainment that makes you think—exactly what Braddon did best.

Her other major works, including Aurora Floyd and The Doctor’s Wife, explore similar themes of women constrained by social expectations and the psychological consequences of those constraints. They’re all page-turners, but they’re also sharp social criticism disguised as popular entertainment.

The Legacy That Should Exist

Mary Elizabeth Braddon should be remembered as one of the most important Victorian novelists, not despite her popularity but because of it. She proved that literature could be both accessible and sophisticated, that commercial success and artistic merit weren’t mutually exclusive.

She created a template for psychological fiction that writers are still following today. She demonstrated that women’s inner lives—including their anger, ambition, and moral complexity—were worthy subjects for serious literature.

Most importantly, she showed that entertainment could be a vehicle for social change. Her novels didn’t just thrill readers—they challenged assumptions about women’s nature, mental illness, and the reality behind domestic respectability.

But maybe what I admire most about Braddon is that she never apologized for writing popular fiction. She never tried to distance herself from her commercial success or claim that she was doing something more elevated than entertainment. She understood that reaching a wide audience was a form of power, and she used that power to tell stories that mattered.

Why She Matters Now

In our current cultural moment, when we’re finally recognizing that “popular” doesn’t always mean “inferior,” Braddon feels relevant. She was writing complex female characters decades before anyone called it feminist literature. She was exploring psychological realism before it became a recognized literary mode. She was proving that genre fiction could be every bit as sophisticated as literary fiction.

She was also a working writer who supported her family through her craft, who understood the commercial realities of publishing while never compromising her artistic vision. In an era when writers are expected to be both artists and entrepreneurs, Braddon’s example of creative and commercial success feels especially valuable.

Reading her work now, you realize that we lost more than just a talented writer when Braddon disappeared from literary history. We lost a model for how to write popular fiction that takes its readers seriously, how to create entertainment that doesn’t condescend to its audience, how to be both commercially successful and artistically ambitious.

We lost proof that the stories women want to read—about domestic violence, psychological manipulation, and the rage that comes from being trapped in impossible situations—have always been worthy of literary treatment.

Lady Audley’s Secret is available free through Project Gutenberg and most e-book platforms. Fair warning: it’s hard to put down, and you might find yourself wondering why your Victorian literature class never mentioned the woman who basically invented the psychological thriller.

Leave a comment