Have you ever been told you had to pick a side? That you couldn’t be all of who you are because it makes other people uncomfortable? That your complexity—your refusal to fit neatly into someone else’s box—is somehow the problem?

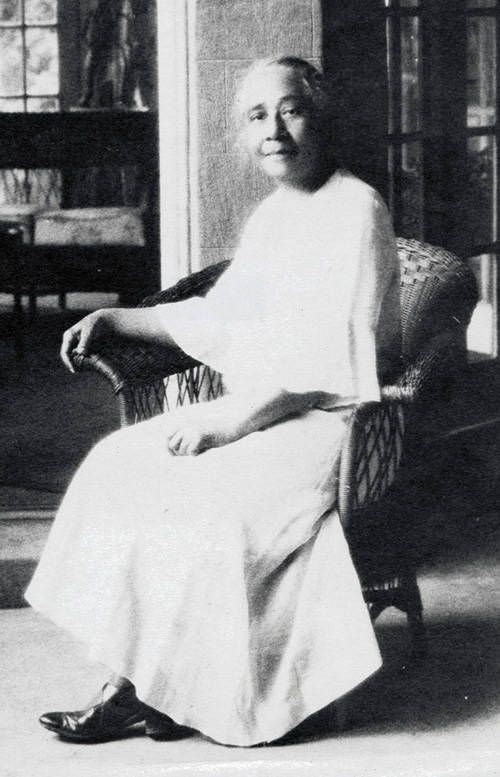

In 1892, a brilliant Black woman named Anna Julia Cooper stood before a room full of white feminists and said something that still shakes that landscape today: “Only the BLACK WOMAN can say ‘when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.’”

She was telling them—and us— that she wouldn’t be fractured. She wouldn’t pretend to be just a woman when it was convenient, or just Black when that served someone’s agenda. She was going to be wholly, completely, and unapologetically herself. And she was going to demand that the world make room for her wholeness.

The Girl Who Wouldn’t Stay in Her Place

Anna Julia Haywood was born around 1858 in North Carolina to an enslaved woman named Hannah Stanley Haywood. Her father was likely her mother’s white enslaver—a reality that Anna would carry throughout her life, not as shame, but as fuel for her understanding of how power, race, and gender intersect in devastating ways.

Young Anna refused to accept the limitations the world tried to place on her. At fourteen, she was already teaching other formerly enslaved people to read and write. By twenty-one, she’d graduated from Oberlin College—one of the few institutions that would admit both women and Black students. She didn’t just survive these spaces; she excelled in them, graduating with honors and demanding more.

But here’s where Anna’s story gets really interesting. She could have settled into respectability. She could have been grateful for her education and kept quiet. But instead, she looked around and asked the question that would define her life: “If I can be here, why can’t others?”

The Voice That Wouldn’t Be Silenced

In 1892, Anna published “A Voice from the South,” a collection of essays that reads like a manifesto for intersectionality, though that term wouldn’t be coined for another century. She wrote with the precision of a scholar and the passion of someone who lived every single word.

She didn’t just critique the world; she dissected it. She examined how white feminists ignored Black women’s experiences, how Black male leaders sidelined women’s voices, and how society tried to force people to choose between their identities. Her writing was surgical—cutting through the comfortable lies that let people avoid confronting their own complicity.

What moves me most about Anna’s work is how she refused to soften her message for anyone’s comfort. When she addressed white women’s right activists, she didn’t beg for inclusion. She demanded it, pointing out that their feminism was incomplete—and fraudulent—if it didn’t account for the experiences of all women.

“The colored woman of to-day occupies… a unique position in this country,” she wrote. “She is confronted by both a woman question and a race problem, and is as yet an unknown or an unacknowledged factor in both.”

The Educator

Anna understood that education isn’t just about individual advancement. It’s about power. It’s about who gets to shape the narrative, who gets to define what knowledge matters, and who gets to participate in the conversations that determine our collective future.

As a teacher and later a principal of M Street High School in Washington, D.C. (now Dunbar High School), Anna didn’t just educate students—she revolutionized what education could look like for Black children. Under her leadership, M Street became a powerhouse, sending more Black students to prestigious universities than any other high school in the country.

But Anna didn’t stop there. At fifty-five years old—an age when most people are thinking about slowing down—she decided to pursue a doctoral degree at the Sorbonne in Paris. Not because she needed the credential, but because she refused to accept that there were doors that should remain closed to her.

She wrote her dissertation in French, on the topic of slavery and attitudes toward race in France. She was the fourth Black woman in American history to earn a PhD, and she did it all while raising five children (including two she’d adopted after their mother died) and working full-time as an educator.

What Makes Anna Julia Cooper Remarkable?

It isn’t her individual achievements—it’s how she used her platform to fundamentally challenge the way we think about identity, justice, and liberation.

She was arguing for intersectionality before we had the language for it. She was talking about how systems of oppression work together to marginalize people at the intersections of multiple identities. She understood that you can’t fight racism while ignoring sexism, and you can’t fight sexism while ignoring racism, because they’re not separate problems. They are part of the same system designed to keep certain people powerless.

This wasn’t an abstract theory for Anna. This was her lived reality. She knew what it felt like to be the smartest person in the room and have people assume she was there to serve coffee. She knew what it felt like to have her expertise questioned, her authority undermined, her very presence seen as an intrusion.

The Price of Being Whole

Being Anna Julia Cooper wasn’t easy. She faced constant resistance from white supremacists who didn’t want Black people educated, from white feminists who wanted to use her but not listen to her, and sometimes from Black male leaders who saw her as a threat to their own authority.

By 1906, she was forced out of her position as principal of M Street High School. The official reasons were vague, but the real reason was clear: she was too independent, too outspoken, too unwilling to compromise her vision of what education could be.

But Anna didn’t retreat. She didn’t apologize for being too much. Instead, she kept teaching, kept writing, kept pushing boundaries. She founded Frelinghuysen University, a night school for working adults. She continued speaking and writing well into her nineties, never losing her fire, and never softening her message.

Why Does Anna Matter Now?

I think about Anna Julia Cooper, especially when I see how we still struggle with these same issues today. How women of color are still asked to choose between fighting racism and fighting sexism. How we’re still told that our complexity is inconvenient, that our refusal to be simple makes us difficult.

Anna shows us that being whole isn’t selfish. When she insisted on being fully herself, she wasn’t just fighting for her own freedom. She was fighting for all of us who refuse to be diminished, all of us who insist that we are more than the sum of society’s prejudices.

She understood that liberation isn’t something you can achieve by fracturing yourself, by hiding parts of who you are to make others comfortable. Real liberation comes from insisting on your full humanity, even when that makes people uncomfortable.

Her Legacy

Anna Julia Cooper lived to be 105 years old, dying in 1964 just as the civil rights movement was reaching its peak. She had lived through slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, two World Wars, and the beginning of the modern civil rights era. She had seen the world change, and she had been apart of its changing.

But her greatest legacy isn’t any single achievement. It’s the example she set of what it looks like to refuse to be diminished. To insist on your own complexity. To demand that the world make room for all of who you are.

In our current moment, when we’re still fighting battles Anna identified more than a century ago, her voice feels more relevant than ever. She reminds us that intersectionality isn’t just an academic concept—it’s a lived reality, a strategy for survival, and a path to liberation.

Anna Julia Cooper didn’t just demand a seat at the table. She demanded that the table be rebuilt to accommodate everyone who had been excluded. And she spent her entire life showing us what that kind of radical inclusion could look like.

When she said, “when and where I enter… the whole Negro race enters with me,” she wasn’t just talking about Black people. She was talking about all of us who have been told we’re too much, too complicated, too difficult to be categorized. She was saying: bring all of yourself. The world needs all of who you are.

Anna Julia Cooper’s “A Voice from the South” remains a foundational text in Black feminist thought and intersectional analysis. Her papers are housed at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, where scholars continue to study her contributions to education, feminism, and civil rights.

Leave a comment