Have you ever felt like you were slowly disappearing? Not dying, but fading—like someone was gradually turning down the volume on your existence until you could barely hear your own voice?

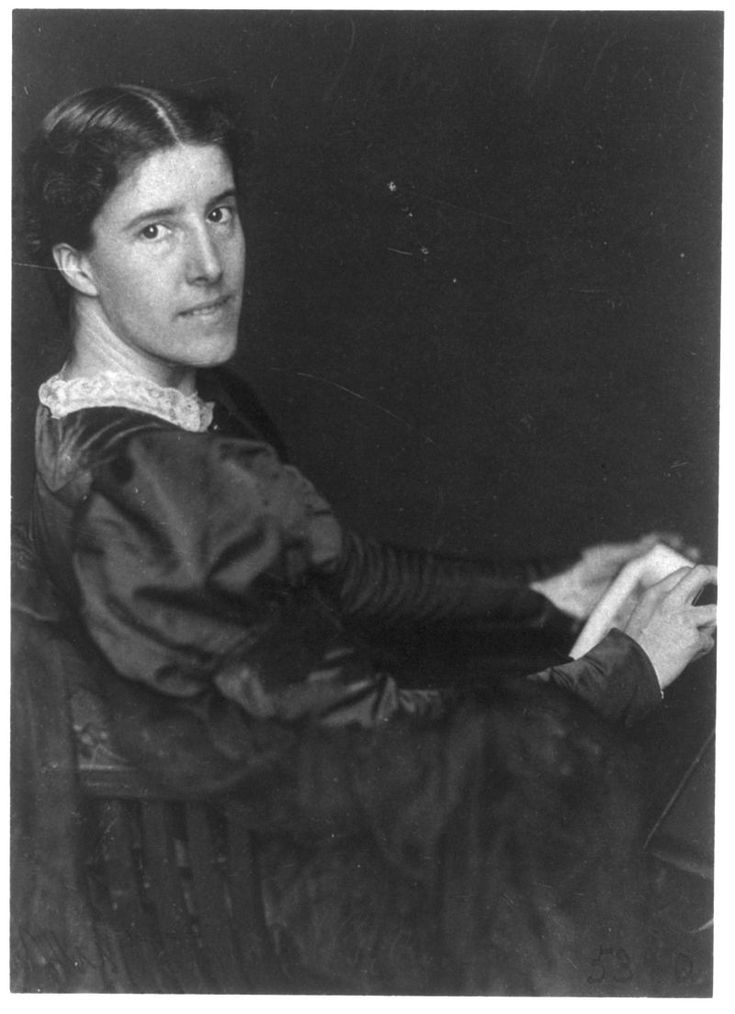

Charlotte Perkins Gilman knew that feeling. In 1887, she was a young mother trapped in what everyone assured her was a perfect life: a loving husband, a beautiful baby, and a comfortable home. She should have been grateful, they said. She should have been happy, they said. But instead, she was dissolving.

The prescribed cure was something called the “rest cure”—six weeks of enforced bed rest, forbidden to write, paint, or engage in any intellectual activity. She was told to “live as domestic a life as possible” and “never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again.” The treatment nearly drove her to what she called “mental ruin.”

But Charlotte didn’t just survive that experience. She weaponized it. She turned her near-destruction into one of the most devastating critiques of women’s subjugation ever written: “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

I Will Not Be Tamed

Charlotte Anna Perkins was born in 1860 into a family that should have prepared her for conventional womanhood. Her father abandoned the family when she was young, leaving her mother to raise Charlotte and her brother in poverty. But instead of teaching Charlotte to depend on men, this experience taught her something far more dangerous: self-reliance.

As a teenager, Charlotte was already rejecting the script written for women of her class. She was athletic when ladies were supposed to be delicate, intellectual when women were supposed to be ornamental, and fiercely independent when society demanded submission. She taught herself to draw, studied economics and philosophy, and dreamed of a career as a writer and reformer.

When she married Charles Walter Stetson in 1884, she thought she could have it all—love, motherhood, and intellectual fulfillment. She was wrong. The combination of domestic expectations, social isolation, and the constant pressure to be grateful for her “natural” role as wife and mother began to crush her spirits.

The Cure That Killed

After the birth of her daughter, Katharine, Charlotte fell into what we would now recognize as postpartum depression. But in 1887, women’s mental health was barely understood, and their intellectual needs weren’t considered at all. Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, the era’s leading expert on “nervous disorders” in women, prescribed his famous rest cure.

The logic was brutally simple: women’s problems stemmed from overstimulation of their delicate nervous systems. The cure was complete intellectual rest—no reading, no writing, no stimulating conversations. Just domesticity, submission, and the slow erasure of self.

Charlotte followed the prescriptions faithfully. For six weeks, she lay in bed, forbidden to engage her mind, while her sense of self slowly disintegrated. She later wrote, “I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the border line of utter mental ruin that I could see over.”

The rest cure didn’t heal Charlotte—it nearly destroyed her. But it also gave her something invaluable: the lived experience of what happens when society systematically denies women their intellectual and creative lives.

The Story That Changed Everything

In 1892, Charlotte published “The Yellow Wallpaper,” a short story that reads like a fever dream and hits like a sledgehammer. On the surface, it’s about a woman slowly going insane while confined to a room with hideous yellow wallpaper. But strip away the gothic elements, and it’s a precise dissection of how women’s voices are silenced, their realities dismissed, and their sanity questioned when they dare to resist.

The unnamed narrator is prescribed the rest cure for her “nervous condition.” Forbidden to write, isolated from intellectual stimulation, she begins to see patterns in the wallpaper—and eventually, a woman trapped behind the pattern, desperately trying to break free.

What makes the story so devastating isn’t just the narrator’s descent into madness. It’s how reasonable her husband sounds throughout, how loving and concerned he appears to be. He’s not a monster—he’s a well-meaning man following the best medical advice of his time. Which makes his destruction of his wife’s sanity all the more horrifying.

The story was too raw, too unsettling for many readers. The Atlantic Monthly rejected it, and when it was finally published, many critics dismissed it as merely a horror story. They missed the point entirely. Charlotte wasn’t writing horror—she was writing realism.

Hiding in Plain Sight

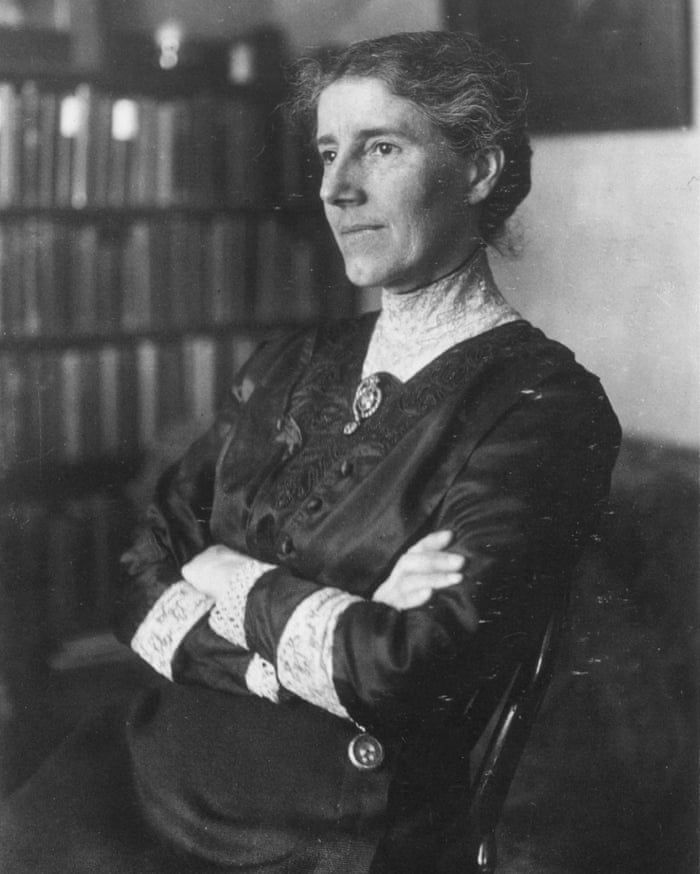

Charlotte transformed her personal trauma into a broader critique of the systems that diminished women. She didn’t just write about her own experience—she analysed the economic, social, and psychological structures that made such experiences inevitable.

In her work, “Women and Economics,” she argued that women’s economic dependence on men wasn’t natural—it was constructed. She showed how the nuclear family, rather than being a haven, could become a prison that stunted women’s development and wasted their talents.

She imagined radical alternatives: communal kitchens that would free women from endless domestic labor, professional childcare that would allow mothers to pursue careers, and economic independence that would make marriage a choice rather than a necessity. These ideas seemed revolutionary in 1898. Some of them still seem revolutionary today.

Speaking Truth

Charlotte’s ideas came at a cost. Her marriage to Charles Stetson couldn’t survive her transformation from submissive wife to radical thinker. In 1894, she did something almost unthinkable: she divorced him and sent their daughter to live with Charles and his new wife (who happened to be Charlotte’s best friend). She chose her sanity and her work over conventional motherhood.

The scandal was enormous. Women who left their husbands were bad enough, but women who gave us custody of their children? That was unforgivable. Charlotte was vilified in the press, criticized by many former friends, and forced to defend her choices for the rest of her life.

But she didn’t apologize. She didn’t retreat. Instead, she threw herself into her work with renewed vigor. She wrote, lectured, and advocated for women’s rights with the passion of someone who had seen the alternative and refused to go back.

The Woman Who Wouldn’t Be Cured

Charlotte inspired many with her refusal to be “cured” of her inconvenient thoughts and feelings. The rest cure was designed to make her a more compliant wife and mother. When it failed, society expected her to find other ways to adjust, to make peace with her diminished existence.

Instead, Charlotte insisted that the problem wasn’t with her—it was with a world that wasted half its human potential by confining women to narrow domestic roles. She didn’t need to be cured; the world needed to change.

This takes breathtaking courage. It’s one thing to recognize that you’re being oppressed. It’s another thing entirely to trust your own perception when everyone around you—including medical experts—is telling you that your feelings are symptoms of illness rather than rational responses to an irrational situation.

Her Legacy

Charlotte Perkins Gilman died in 1935, having chosen to end her life rather than endure the slow progression of breast cancer. Even in death, she refused to submit to forces beyond her control. Her suicide note read, “I have preferred chloroform to cancer.”

But her real legacy isn’t how she died—it’s how she lived. She showed us what it looks like to transform personal pain into political insight, to refuse to be “cured” of inconvenient truths, and to trust your own experience even when the experts tell you it’s pathological.

“The Yellow Wallpaper” remains one of the most taught stories in American literature, not because it’s a quaint historical curiosity, but because it still speaks to women’s experiences today. How many of us have been told that our dissatisfaction with limiting roles is a personal problem rather than a political one? How many of us have been prescribed rest, medication, or therapy when what we really need was freedom?

Her Impact

I think about Charlotte when I encounter the modern versions of the rest cure—the wellness culture that tells women their problems stem from not being grateful enough, the self-help industry that promises happiness through better self-management, the persistent message that if we’re not thriving in systems designed to diminish us, the problem must be with us.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman reminds us that sometimes the most radical thing you can do is trust your own perception. Sometimes your dissatisfaction isn’t a symptom to be cured—it’s information to be considered. Sometimes the pattern you see in the wallpaper isn’t madness—it’s simply clarity.

She refused to wallpaper over the cracks in a system that wasted women’s lives. Instead, she tore the wallpaper down and showed us what was behind it. Not monsters, but women trying to break free. And in doing so, she gave us permission to do the same.

The woman trapped behind the pattern in “The Yellow Wallpaper” finally breaks free, even if it costs her sanity. Charlotte broke free too, and kept her sanity by refusing to pretend that an insane world was sane. That might be the most revolutionary act of all.

Leave a comment